Human overpopulation

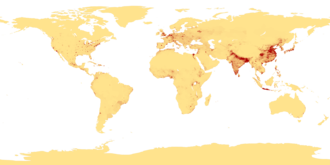

Human overpopulation (or population overshoot) is a state in which there are too many people for the environment to sustain (with food, drinkable water, breathable air, etc.). In more scientific terms, there is overshoot when the ecological footprint of a human population in a geographical area exceeds that place's carrying capacity, damaging the environment faster than it can be repaired by nature, potentially leading to an ecological and societal collapse. Overpopulation could apply to the population of a specific region, or to world population as a whole.[1]

Overpopulation can result from an increase in births, a decline in mortality rates, an increase in immigration, or an unsustainable biome and depletion of resources.

Advocates of population moderation cite issues like exceeding the Earth's carrying capacity, global warming, potential or imminent ecological collapse, impact on quality of life, and risk of mass starvation or even extinction as a basis to argue for population decline.

A more controversial definition of overpopulation, as advocated by Paul Ehrlich, is a situation where a population is in the process of depleting non-renewable resources. Under this definition, changes in lifestyle could cause an overpopulated area to no longer be overpopulated without any reduction in population, or vice versa.

Scientists suggest that the overall human impact on the environment, due to overpopulation, overconsumption, pollution, and proliferation of technology, has pushed the planet into a new geological epoch known as the Anthropocene.

- "An expansion of the demographic transition model: the dynamic link between agricultural productivity and population" (PDF). Russel Hopfenberg, Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences Department, Duke University, USA. Journal Biodiversity, Taylor & Francis Online.

- "I Am the Population Problem?". Rewire.

- "Too much food, too many people on a finite planet". Steven Earl Salmony. The Herald Sun.

- "Overpopulation, overconsumption – in pictures". The Guardian.

- "Why we should have fewer children: to save the planet". The Guardian.

- "Overpopulated and Underfed: Countries Near a Breaking Point". Bill Marsh. The New York Times.

- "Earth's sixth mass extinction event under way, scientists warn". The Guardian. "But the ultimate cause of all of these factors is "human overpopulation and continued population growth, and overconsumption, especially by the rich", say the scientists."

- Pan Earth- a content of videos and articles on the causes and consequences of human overpopulation.

- "The Psychology of Denying Overpopulation". Douglas T. Kenrick. Psychology Today. September 13, 2020.

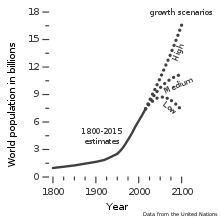

World population has been rising continuously since the end of the Black Death, around the year 1350.The fastest doubling of the world population happened between 1950 and 1987: a doubling from 2.5 to 5 billion people in just 37 years, mainly due to medical advancements and increases in agricultural productivity.

Due to its dramatic impact on the human ability to grow food, the Haber process served as the "detonator of the population explosion," enabling the global population to increase from 1.6 billion in 1900 to 7.7 billion by November 2018.

History of concern ::-

Concern about overpopulation is an ancient topic. Tertullianwas a resident of the city of Carthage in the second century CE, when the population of the world was about 190 million (only 3–4% of what it is today). He notably said: "What most frequently meets our view (and occasions complaint) is our teeming population. Our numbers are burdensome to the world, which can hardly support us... In very deed, pestilence, and famine, and wars, and earthquakes have to be regarded as a remedy for nations, as the means of pruning the luxuriance of the human race." Before that, Plato, Aristotle and others broached the topic as well.

Throughout recorded history, population growth has usually been slow despite high birth rates, due to war, plagues and other diseases, and high infant mortality. During the 750 years before the Industrial Revolution, the world's population increased very slowly, remaining under 250 million.

By the beginning of the 19th century, the world population had grown to a billion individuals, and intellectuals such as Thomas Malthus predicted that humankind would outgrow its available resources because a finite amount of land would be incapable of supporting a population with limitless potential for increase.Mercantillists argued that a large population was a form of wealth, which made it possible to create bigger markets and armies. The rich have always known that the real value of their fortune is "how much labor will it purchase?" This because almost all things humans value are only frozen labor. So the more numerous and poorer the population, the less those workers can charge for their labor.

During the 19th century, Malthus' work was often interpreted in a way that blamed the poor alone for their condition and helping them was said to worsen conditions in the long run.This resulted, for example, in the English poor laws of 1834and a hesitating response to the Irish Great Famine of 1845–52.

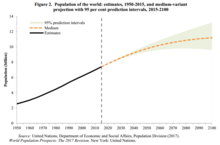

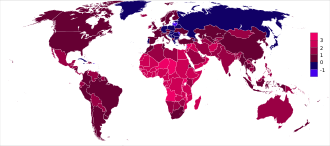

The UN publication 'World population prospects' (2017) projects that the world population will reach 9.8 billion in 2050 and 11.2 billion in 2100. The human population is predicted to stabilize soon thereafter.

A 2014 study published in Science asserts that population growth will continue into the next century.Adrian Raftery, a University of Washington professor of statistics and sociology and one of the contributors to the study, says: "The consensus over the past 20 years or so was that world population, which is currently around 7 billion, would go up to 9 billion and level off or probably decline. We found there's a 70 percent probability the world population will not stabilize this century. Population, which had sort of fallen off the world's agenda, remains a very important issue." UN projections from 2011 suggest the population could grow to as many as 15 billion by 2100.

In 2017, more than one-third of 50 Nobel prize-winning scientists surveyed by the Times Higher Education at the Lindau Nobel Laureate Meetings said that human overpopulation and environmental degradation are the two greatest threats facing humankind.In November that same year, a statement by 15,364 scientists from 184 countries indicated that rapid human population growth is the "primary driver behind many ecological and even societal threats."

In spite of concerns about overpopulation, widespread in developed countries, the number of people living in extreme poverty globally shows a stable decline (this has been disputed by some experts), even though the population has grown seven-fold over the last 200 years. Child mortality has declined, which in turn has led to reduced birth rates, thus slowing overall population growth.The global number of famine-related deaths have declined, and food supply per person has increased with population growth.

In 2019, a warning on climate change signed by 11,000 scientists from 153 nations said that human population growth adds 80 million humans annually, and "the world population must be stabilized—and, ideally, gradually reduced—within a framework that ensures social integrity" to reduce the impact of "population growth on GHG emissions and biodiversity loss."

History of population growth ::-

World population has gone through a number of periods of growth since the dawn of civilization in the Holocene period, around 10,000 BCE. The beginning of civilization roughly coincides with the receding of glacial ice following the end of the last glacial period. I is estimated that between 1–5 million people, subsisting on hunting and foraging, inhabited the Earth in the period before the Neolithic Revolution, when human activity shifted away from hunter-gathering and towards very primitive farming.

Around 8000 BCE, at the dawn of agriculture, the human population of the world was approximately 5 million. The next several millennia saw a steady increase in the population, with very rapid growth beginning in 1000 BCE, and a peak of between 200 and 300 million people in 1 BCE.

The Plague of Justinian caused Europe's population to drop by around 50% between 541 and the 8th century. Steady growth resumed in 800 CE. However, growth was again disrupted by frequent plagues; most notably, the Black Deathduring the 14th century. The effects of the Black Death are thought to have reduced the world's population, then at an estimated 450 million, to between 350 and 375 million by 1400.The population of Europe stood at over 70 million in 1340; these levels did not return until 200 years later.England's population reached an estimated 5.6 million in 1650, up from an estimated 2.6 million in 1500. New crops from the Americas via the Spanish colonizers in the 16th century contributed to the population growth.

Significant increases in human population occur whenever the birth rate exceeds the death rate for extended periods of time. Traditionally, the fertility rate is strongly influenced by cultural and social norms that are rather stable and therefore slow to adapt to changes in the social, technological, or environmental conditions. For example, when death rates fell during the 19th and 20th century – as a result of improved sanitation, child immunizations, and other advances in medicine – allowing more newborns to survive, the fertility rate did not adjust downward, resulting in significant population growth. Until the 1700s, seven out of ten children died before reaching reproductive age. Today, more than nine out of ten children born in industrialized nations reach adulthood.

Population as a function of food availability ::-

Many people from a wide range of academic fields and political backgrounds—including agronomist David Pimentel, behavioral scientist Russell Hopfenberg, anthropologist Virginia Abernethy, ecologist Garrett Hardin, science writer and anthropologist Peter Farb, journalist Richard Manning, environmental biologist Alan D. Thornhill, cultural critic and writer Daniel Quinn, and anarcho-primitivist John Zerzan, —propose that, like all other animal populations, human populations predictably grow and shrink according to their available food supply, growing during an abundance of food and shrinking in times of scarcity.

Critics of this theory point out that, in the modern era, birth rates are lowest in the developed nations, which also have the highest access to food. In fact, some developed countries have both a diminishing population and an abundant food supply. The United Nations projects that the population of 51 countries or areas, including Germany, Italy, Japan, and most of the states of the former Soviet Union, is expected to be lower in 2050 than in 2005. This shows that, limited to the scope of the population living within a single given political boundary, particular human populations do not always grow to match the available food supply. However, the global population as a whole still grows in accordance with the total food supply and many of these wealthier countries are major exporters of food to poorer populations, so that, "it is through exports from food-rich to food-poor areas (Allaby, 1984; Pimentel et al., 1999) that the population growth in these food-poor areas is further fueled.

Regardless of criticisms against the theory that population is a function of food availability, the human population is, on the global scale, undeniably increasing, as is the net quantity of human food produced—a pattern that has been true for roughly 10,000 years, since the human development of agriculture. The fact that some affluent countries demonstrate negative population growth fails to discredit the theory as a whole, since the world has become a globalized system with food moving across national borders from areas of abundance to areas of scarcity. Hopfenberg and Pimentel's findings support both this and Quinn's direct accusation that "First World farmers are fueling the Third World population explosion."

No comments:

Post a Comment